Oxalate: a piece of the health puzzle

Jul 1, 2020

Posted by: Monique Parker

Spinach, blueberries, beetroot, kiwi, nuts, cocoa, tahini, turmeric, sweet potato..….

Healthy foods that many of you will probably consume on a daily basis. But apart from being ‘healthy foods’ there is another common denominator: they are all very high in oxalates.

Oxalate, or oxalic acid, is an organic substance that is found in plants, usually bound to minerals such as calcium. Only 20-40% of the oxalates in our blood come from the foods we eat.[i]

It can also be produced by the body. For example, through the conversion of vitamin C into oxalate when it is broken down in the body.[ii] So, there are two main sources of oxalate: from what we eat and what we produce ourselves.

The reason why I would like to draw attention to these highly reactive molecules is because of a personal experience.

The reason why I would like to draw attention to these highly reactive molecules is because of a personal experience.

A couple of months ago I did an organic acid test. Organic acids are chemical compounds that are excreted in urine and that are products of metabolism (the chemical reactions in the body's cells that change food into energy). To my surprise, all three oxalate markers were high. As a nutritional therapist, I immediately thought of what my food pattern had

been recently and what my gut health was like at that moment.

Being health-conscious, I had been eating quite a bit of spinach, lots of nuts (my favourite snack), my daily portion of berries, my evening treat -a small piece of dark chocolate, and the rhubarb that had been quite prolific on the allotment this year, resulting in a lot of recipe experimenting during lockdown. All very high-oxalate foods.

Rhubarb is the most concentrated source of preformed oxalates. Chocolate can also be a concentrated source; the higher the percentage of cocoa, the higher the oxalate content (oh dear, I eat 85% + dark chocolate). I had also increased my vitamin C intake because of Covid-19.

For quite a while, I had been experiencing fatigue, painful joints and occasionally I had excruciating pain in my big toes at night, like someone was sticking needles in them. Could the oxalate have anything to do with this?

Going back to my books and revisiting ‘oxalates’ again was quite an eye opener.

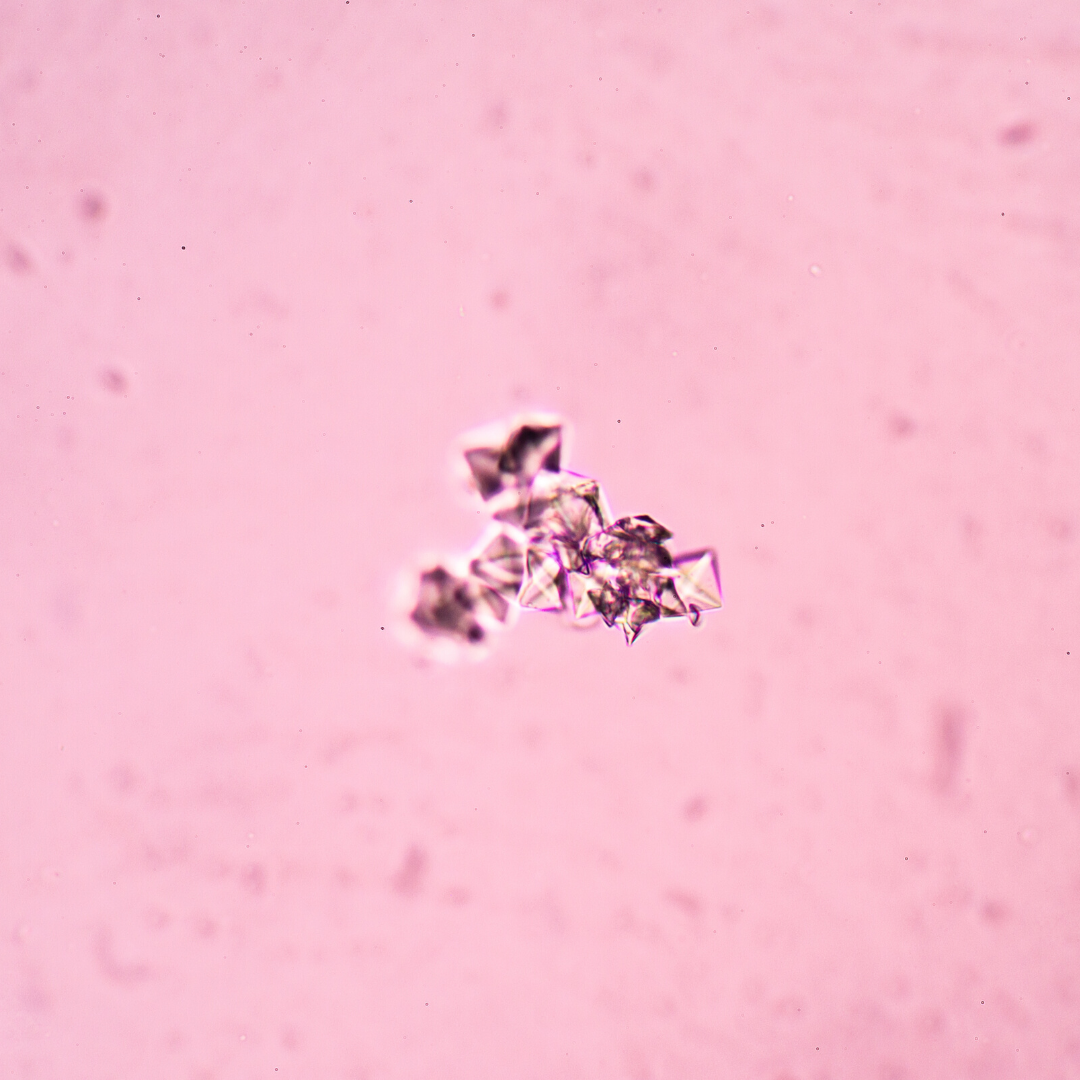

Oxalate, famous for formation of calcium oxalate kidney stones (this is oxalate bound to calcium), can mess with the function of your cells when it is free, unbound. So apart from being able to cause kidney stones, it could also cause fatigue, inflammation, joint pain, and a whole host of other symptoms. The oxalates can show up in our body as sharp crystals that cause pain and irritation.

There is even a condition called ‘Oxalate Crystal Disease’ where calcium oxalate crystal deposition can occur within a variety of tissues. [iii] Because oxalates can affect mitochondrial function[iv] and can create inflammation, they can affect every system of the body.

Oxalates can bind to minerals such as calcium, magnesium, iron, or copper, to form compounds, that are normally eliminated in the stool or urine.

It is worth mentioning that because oxalate likes to bind to minerals, they can inhibit the absorption. The minerals that you take in through your food are captured by the oxalate and won’t be well absorbed in the gut. This could lead to someone having a mineral deficiency.

If you are regularly consuming high oxalate foods and are feeling ok, you are probably asking yourself why you never experienced any problems, given calcium oxalate crystals can cause so much trouble.

Everyone is unique, and this also counts for how we process oxalate.

If you have a vitamin B6[v] deficiency for instance, you could be producing oxalate yourself, as vitamin B6 is needed to breakdown an organic compound in the body (glyoxylate) and if there is not enough vitamin B6, the glyoxylate will turn into oxalate instead of glycine.[vi]

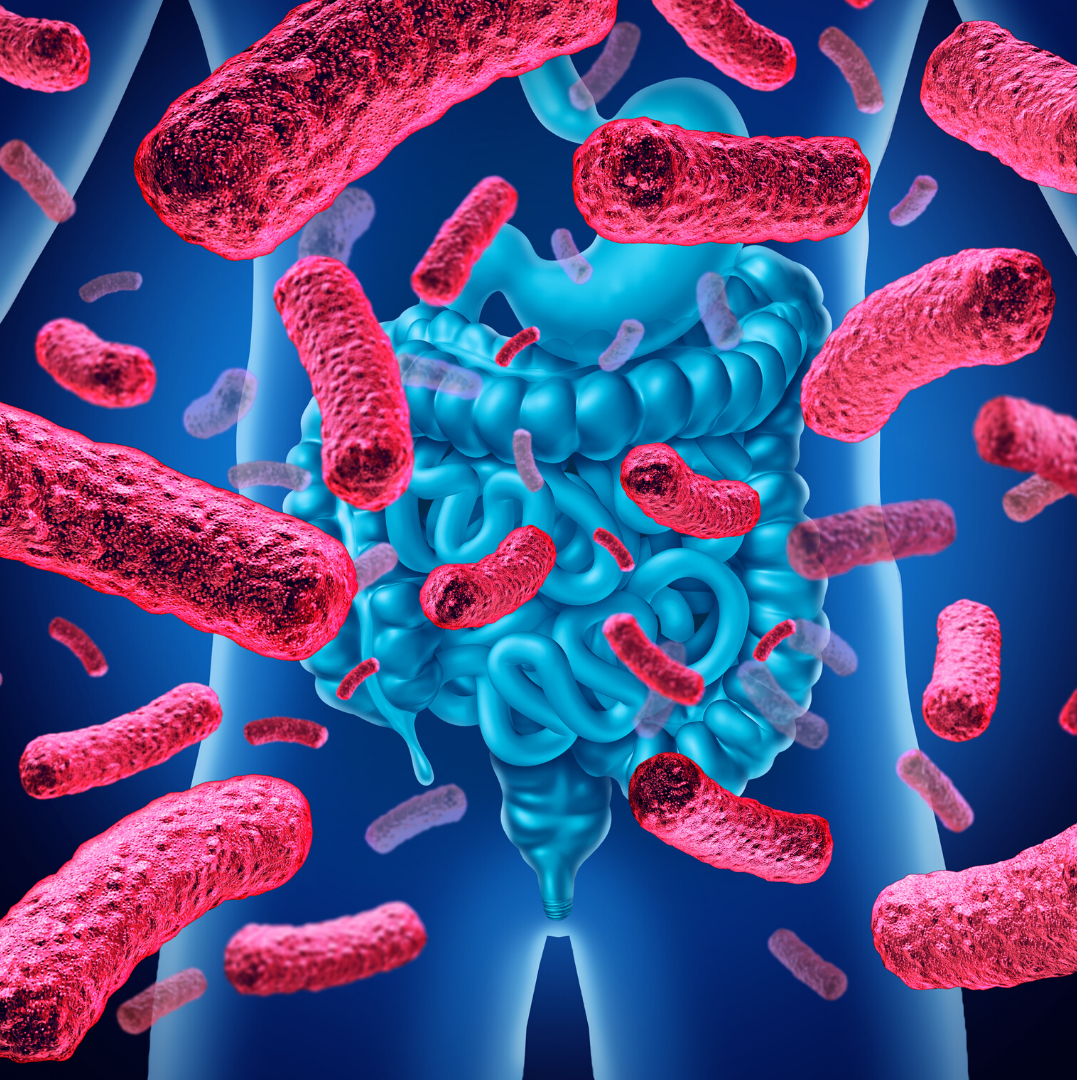

If you have gut problems, there might not be enough bacteria to break the oxalate down. Or someone has not got enough minerals for the oxalate to bind with and it can be freely absorbed in the body. Also, we all have a different body chemistry and genetic makeup that could affect how we process oxalates.

If you have a healthy gut, there won’t be a lot of oxalate absorption. Most of the oxalate from what you are eating will be metabolised by gut bacteria, or it will be eliminated in the stool. Although the minerals in the compounds are lost, at least the oxalate won’t end up in the bloodstream and wreak havoc in the body.

Gut dysbiosis is a problem, as certain bacteria, i.e. Oxalobacter formigenes, Lactobacillus acidophilus or various species of Bifidobacteria, can break down oxalate. [vii] [viii] So, you need healthy gut flora, including these beneficial ones.

Gut dysbiosis is a problem, as certain bacteria, i.e. Oxalobacter formigenes, Lactobacillus acidophilus or various species of Bifidobacteria, can break down oxalate. [vii] [viii] So, you need healthy gut flora, including these beneficial ones.

‘Leaky Gut’ is another problem, where the oxalate slips through the ‘leaky’ junctions in the gut lining, into the blood stream. And then there is also the possibility of the oxalates being byproducts of fungi such as Aspergillus and possibly Candida.

For most people who are not at risk of calcium oxalate kidney stone formation—or do not have any of the unusual health conditions that need strict oxalate restriction— oxalate-containing foods should not be a problem.

If you’re interested to know the oxalate content of different foods, here is the link to an extensive food chart http://www.lowoxalate.info/food_lists/alph_oxstat_chart.pdf

Please don’t start panicking when you see how many foods are high in oxalate, as it is not always bad news. For instance, black tea has 156mg of oxalate in 200ml (green tea only has 80mg/200ml).[ix] Although this means that people who easily get kidney stones should drink black tea in moderation, for other people drinking black tea on a daily basis, it will mean there will be a moderate intake of oxalate each day, however, if you drink the tea with milk, very little oxalate will be absorbed from tea.[x]

Going back to my own experience, I decided to dramatically lower my intake of high-oxalate foods, which wasn’t easy. But it paid off, as I’m not as tired as I was before, less joint pain, and I haven’t experienced any stabbing pain in my big toes since. I guess I was lucky to find out, by coincidence, that my oxalate levels were high. The Organic Acid Test was done for something unrelated. So, I found that missing piece of the puzzle.

If you have any niggling health issues such as fatigue or aches and pains that your GP can’t explain, it is worth looking into your oxalate food intake and maybe do an oxalate urine test (available as a home test, but make sure you don’t take any vitamin C for 24 hours before the test). And of course, think about your gut health.

Qualified nutritional therapists can support you with all this.

References

[i] Noonan & Savage (1999), Oxalate Content of Foods and Its Effect on Humans, Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 8(1):64-74

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24393738/

[ii]Olivier Traxer et al (2003), Effect of Ascorbic Acid Consumption on Urinary Stone Risk Factors, J Urol (2 Pt 1):397-401

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12853784/

[iii]Elizabeth Lorentz et al (2013), Update on Oxalate Crystal Disease, Curr Rheumatol Rep.15(7): 340

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3710657/pdf/nihms478850.pdf

[iv] Josephine Veena et al (2008), Mitochondrial dysfunction in an animal model of hyperoxaluria: a prophylactic approach with fucoidan. European Journal of Pharmacology 579(1), 330-336

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0014299907011338

[v] Rao & Choudhary (2005), Effect of pyridoxine (Vitamin-B6) supplementation on calciuria and oxaluria levels of some normal healthy persons and urinary stone patients, Indian J Clin Biochem. 20(2): 166–169

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3453845/

[vi] Saori Nishijima et al (2006), Effect of Vitamin B6 Deficiency on Glyoxylate Metabolism in Rats With or Without Glyoxylate Overload, Biomed Res 27(3):93-8

https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/biomedres/27/3/27_3_93/_article

[vii] Marguerite Hatch (2017), Gut microbiota and oxalate homeostasis, ATM Vol 5, No 2

http://atm.amegroups.com/article/view/13316/13679

[viii] Sylvia Duncan et al (2002), Oxalobacter formigenes and Its Potential Role in Human Health, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, p. 3841– 3847

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC124017/pdf/0247.pdf

[ix] Justyna Brzezicha-Cirocka et al (2016), Oxalate, magnesium and calcium content in selected kinds of tea: impact on human health, European Food Research and Technology volume 242, p. 383–389

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00217-015-2548-1

[x] Savage et al (2003), Bioavailability of soluble oxalate from tea and the effect of consuming milk with the tea, European Journal of Clinical Nutrition volume 57, p. 415–419

https://www.nature.com/articles/1601572.pdf

http://www.whfoods.com/genpage.php?tname=george&dbid=48

https://bioindividualnutrition.com/oxalates-their-influence-on-chronic-disease/

http://www.lowoxalate.info/index.html

https://articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2019/11/10/oxalic-toxicity.aspx